It's Not Just About Food

A final Orecchiette con le cime di rapa in Bari, Italy after two years of chemo

Dear Elyse,

Remember when I told you that when this is all over we’re going to take a trip? Then welcome to Bari, Italy! We are warm and happy on the Adriatic sea. We made it. You are done with chemo. We never have to go to the hospital together again. So let’s enjoy it. We’re celebrating because today I turned in my new book. It’s about food. But also, I mean, about feelings and stuff.

It has been more than two years since you started chemo. Nine months since your oncologist said they would not move forward with your treatment. It has been three months since we cleaned out your apartment. Two months since we planted your memorial-tree in Prospect Park.

I still miss you every day. My new agent really likes the book. He said it would be better if I could learn to open up more. So I’m gonna try.

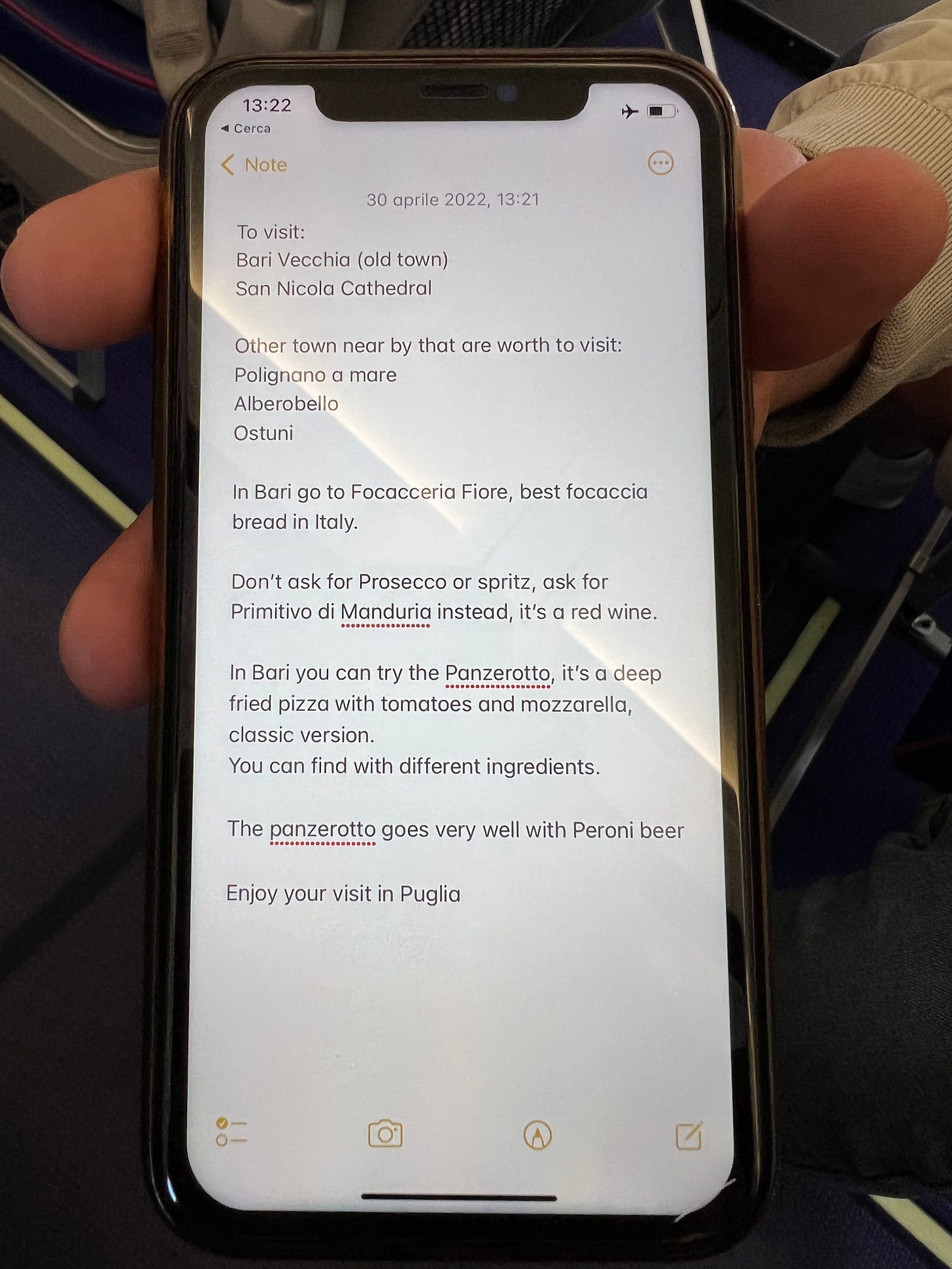

I was crying in the Exit row on the flight here and a guy across the aisle, unprompted, handed me a list of Bari recommendations. I was holding the last bit of your ashes at the time. And I’m going to leave them here in Bari. So tonight let’s take his recommendations. We’ll get dinner and I’ll tell you a story from the new book.

When I told him of my rather morbid task he asked how how we met. I just lit up. A friend’s mom emailed saying her friend’s daughter just moved to the City. “It’s her birthday this weekend, do you think you could invite her to something?” I invited you out with my friends at Floyd’s on Atlantic Avenue in Brooklyn 17 years ago and *boom*—instant best friend. I haven’t planned my own birthday dinner since the 2000s.

You were at my Christmas party when you got the call that you had cancer. I remember I saw you in the backyard crying on the phone with no coat on. On Monday I sent an Uber to pick you from your biopsy at Sloan Kettering. I made the car pick me up so we could get lunch at Lobo in Carroll Gardens. That part was my idea. They wouldn’t deliver to your new apartment so I used to bring you their tortilla soup on sick days. That was our last meal together. Until now.

Tonight we’re going to get a pasta called Orecchiette con le Cime di Rapa, the signature dish of Puglia. Bari is a fun and ancient port city with narrow, winding streets that meander to the 11th century Basilica of St. Nicholas. His picture is everywhere. We haven’t had a care-free time since my Christmas party in 2019 and tonight we’'ll walk around a city with historic murals built for Santa Claus.

I’ll take you to the “Strada delle Orecchiette” where old women make the Orecchiette “little ear” pasta on folding card tables in the ancient streets. In the morning a humid breeze comes in from the Adriatic sea, later a cooler breeze comes down from the mountain and dries the pasta to perfection. The little ears whisper in the wind as they tremble on handmade drying screens.

Orecchiette is a staple here in Puglia. It comes from the “strascinati” family of pastas, from the Italian verb “to drag.” They roll it out by hand into a little dough-rope and then cut it up into bite sized portions, like gnocchi. Then they drag each little dumpling towards them on the table with a simple butter knife then flip the shape inside out. You basically have a cavatello-like shape and it becomes orecchiette when they peel it off the knife. The dragging motion forms rough ridges that cling to every drop of sauce.

Be on the lookout for the smokey “grano arso” flour made of toasted wheat for something you can really only get in Puglia. I’ll bring a bag home for your mom.

The key to Orecchiette con le Cime di Rapa is to cook down some broccoli rabe until it becomes kind of ragù with garlic, anchovies, red pepper, white wine and pecorino. The result is slightly bitter and rich.

Bitterness is only temporary in life. Having a friend like you made the bitter events of our 20s almost enjoyable. Break ups, getting fired, bad news, the loss of a pet or a family member—these all have a way of defining an era in our lives. The hope is that the bitterness is temporary and it forces you to change without letting it make you bitter. But it helps bring things to an end. Think of the bitterness of the vanilla in a crème brûlée, made easier with some sugar and milk. Or an espresso after a big meal. The palette cleansing sherbert they served in the middle of dinner at Prom. Amarro, negroni, dark chocolate. You get the idea.

At Christmas I didn’t know that you’d been sick for a while and suffered from the two worst things in American healthcare. You were between jobs when you got sick but your health insurance didn’t kick in until you stayed at the new job for three months. And then, cherry on top, you met your insurance deductible for the year in December and then it reset in January.

Anyway, So let’s sit down and order. I’m gonna get us a bottle of that Primitivo di Manduria my seatmate recommended.

It has a sort of red berry flavor with a hint of vanilla and great tannic structure—bitterness in action.

Do you like it? Good.

I want to tell you a story from my new book.

In March 1942 an American doctor from New Jersey named Stewart Francis Alexander made a stunning discovery when he got a lab sample of some new liquid mustard gas smuggled out of a Nazi lab. The government wanted him to figure out what symptoms to look for if they used any of it, since the Geneva Conventions outlawed mustard gas.

Dr. Alexander tested it on rabbits and found that their white blood cells dropped to zero. The effect was so uniform that he wrote in his lab notes “bad batch of rabbits.” Science never churns out a 100% result. So they tried it on a menagerie of guinea pigs, rats, mice and even goats. They found the same results.

Even in 1942 Alexander wondered what would happen if he could use this “nitrogen mustard” on humans. Children, for example, frequently died from leukemia—a form of blood cancer. But no way would the US government let him just dose a bunch of people with mustard poison. Even if he could get volunteers, he would need to poison thousands of people to get a reliable sample of data.

Which is why I’ve brought us to Bari, Italy.

On December 2, 1943 the German Air Force destroyed 27 American cargo ships in the port city of Bari, Italy. 1000 people were either killed or injured. The anchored vessels were lined up like sitting ducks and picked off one by one in a low-level attack at dawn.

Most of the ships carried supplies to feed the local population starved out by war. One of the ships, the SS John Harvey, carried an unfortunate secret onboard in the form of 100 tons of Top Secret American-made mustard gas. So in addition to the bombing at sea, a cloud of mustard gas sprayed over the allies and civilians in the surrounding area. And no one knew what it was.

Because the mystery agent had spread at the same time, symptoms appeared en masse on the wounded. It was as if their symptoms appeared in sync on a timer. Nurses reported that men at dawn complained of painful thirst after the drinks cart came around. Suddenly all the men would clamor for water. Then they began yelling that they felt an intense heat and a mass of them began tearing off their clothing and bandages.

Before they could accuse the Nazis of dropping mustard gas they would need proof.

They needed to call in an expert and the one to take their call was none other than our white blood cell expert from New Jersey, Dr. Stewart Francis Alexander.

On December 7, 1943, five days after the attack on the port of Bari, Dr. Alexander’s plane touched down at the city airfield.

He thought that the injuries could have happened if the Nazis dropped a mustard gas bomb and timed it to go off 200 feet above. But if that were true he would find evidence of it on all ships in the harbor, not just a few. Soon the civilians in town had similar symptoms without a single cause. Dr. Alexander wanted them checked for the new Nitrogen Mustard Gas.

With the burden of proof on him he ordered both tests and autopsies. He knew he couldn’t save many of the patients. But their deaths could go on to save countless lives in the future if they could study them in time. Then he ordered blood tests and they came back like his laboratory rabbits—a huge drop in white blood cells.

After 10 days he wrote up a report. Everyone worried that Hitler, with his back to the wall, might go all out and release a chemical weapon stockpile. So Churchill and FDR silenced the report. But not before it got one more reader. Col. Cornelius P. “Dusty” Rhoads, chief of the Medical Division of the Chemical Warfare Service was in civilian life the head of New York’s Memorial Hospital for the Treatment of Cancer and Allied Diseases.

Rhoads persuaded Alfred P. Sloan Jr., the chairman of General Motors, along with the company’s wizard engineer, Charles F. Kettering, to endow a new institute that would study what happened in Bari. He wanted leading scientists and physicians to make a concentrated attack on cancer. Nitrogen mustard and Dr. Alexander’s patients led to the process of chemotherapy. According to the Smithsonian: “On Tuesday, August 7, 1945, the day the world learned that an atom bomb had been dropped on Japan, they announced their plans for the Sloan Kettering Institute for Cancer Research. World War II was over, but the war on cancer had just been launched.”

They renamed it Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, the hospital that gave us two more years as friends.

🛬

I know that because I’m American I’m supposed to say something about how good can come from war. How bad things can actually be good. And blah blah blah. I’m not. War is stupid. Chemo sucks ass. The thing I want to say is that what I learned this year is that surviving is enough. Survival is a skill. You do it one day at a time. And sometimes when you go through hell it’s your job to tell people that there’s something on the other side. So that they keep going too.

You survived 2020 for us. You made it through 2021. We got to 2022 together. And that is enough.

Grief is just the place that love goes when it gets lost. It is a bitter flavor in search of company that it may never find. You made me promise that I wouldn’t grieve forever. That I would live life and enjoy things here on Earth. So I am going to leave you here in the Bari Harbor.

I don’t want to say goodbye. But I love you and I would do anything for a friend. I hope you like it here in Italy. It’s warm, sunny. You will never have to go to the hospital again. I promise I’ll come visit.

We just finished dinner. So I will say goodnight to you, sweet friend.

I will think of you whenever I have Orechiette con Cime di Rapa.

And may god hold you in the palm of her hand until we meet again.

Just beautiful Brendan.

Your words paint a deeply moving picture. Thank you for sharing.